The History of Glass in the Lusatian Mountain Region

By Jaroslav Rež (in cooperation with Michal Gelnar)

Content:

- Introduction

- Medieval Glass Industry

- Renaissance

- Baroque

- Glass In the 19th Century

- Industrial Expansion in the Second Half of the 19th Century and in the First Half of the 20th Century

- The Present

- Supplement

- Literature

- On Authors

Introduction

The tradition of glass making in the Lusatian Mountains is more than seven hundred years old. During its long history there were several periods when this quiet region in the north of Bohemia went down in the world history of this extraordinary craft. More serious and intensive research into the history of glass making in this region has been made from the early 1960's by Václav Sacher from the Museum of Glass in Nový Bor. His activities were followed by young and middle-aged generations of researchers.

Medieval Glass Industry

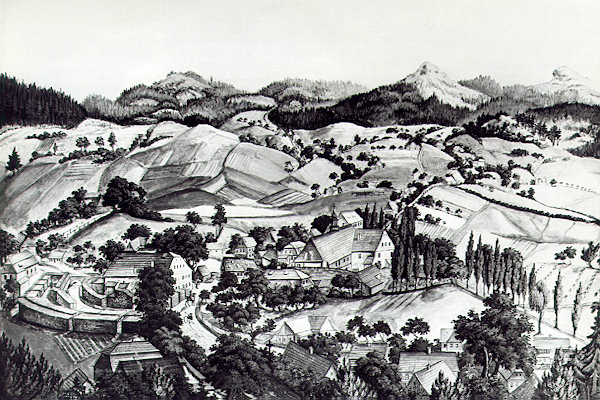

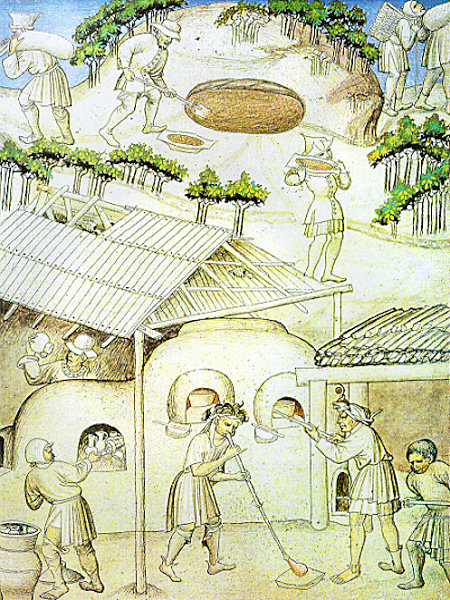

Like other border-forming mountain ranges in medieval Bohemia, the Lusatian Mountains were a mere abandoned forest. Thanks to abundant stocks of wood - used as both fuel and a raw material - later owners of this territory found glass making a suitable way to exploit this otherwise deserted area. The Lusatian Mountains are further marked with a significant geological defect known as the 'Lusatian break' which is scattered with quartz veins. Crushed quartz was one of the basic raw materials used in the melting of glass. This is why the oldest medieval glass making shops were founded immediately in those locations rich with necessary raw materials. When the reserves of wood within accessible reach of a glassworks were exhausted, a new glass making center was situated further away. Therefore, a typical medieval glassworks changed its location several times during its existence. It is also assumed that glass making activities in the Lusatian Mountains were a purposeful vanguard of the subsequent colonisation of villages. Some villages in this region were founded directly on the sites previously cleared for the working of glassworks.

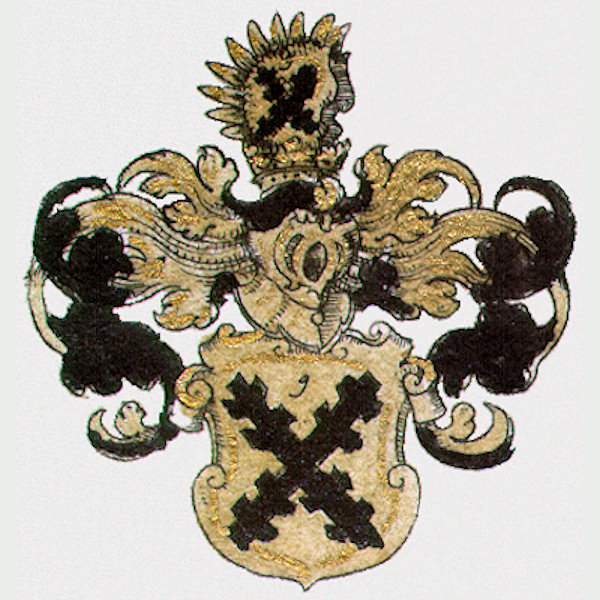

The local medieval glassworks were erected

only in areas under the rule of the House of Ronovec, and later by that branch

of their lineage that was known as the Berks of Lipá (of Dubá). This implies

a possible connection of the beginnings of the regional glass industry with

this notable Bohemian dynasty. At the same time the House of Ronovec owned vast

territories spreading from the North of Bohemia to the South of the country,

including areas located in the today's Germany.

The two oldest glassworks were founded in

the middle of the Lusatian Mountains at the southern foot of Bouřný (703 m above

sea level), next to a secluded settlement known as Nová Huť, north of the village

of Svor. Their history dates back to about 1250. Today, these two glassworks

are considered to be the oldest glass-making centers ever situated in Bohemia.

Other glassworks in the Lusatian Mountains dated back to the turn of the 13th century, and are found in the vicinity of a settlement called Lesná or of the villages of Dolní Světlá and Horní Světlá. In the first half of the 15th century glassworks were established in the western part of the Lusatian Mountains, namely in Doubice and near Horní Chřibská. These glassworks have been traditionally labeled as the predecessors of the still fully-functional glassworks in Horní Chřibská, which is taken for the oldest operating glassworks in Central Europe. However the year 1414, which is mentioned as its establishment date, is only symbolic as the precise date of its foundation is not known. Medieval glassworks were also built on the sites of other villages such as Trávník, Drnovec, Kytlice (formerly Falknov); in the settlement of Rozhled near Jedlová Mountain (774 m above sea level); and in the vicinity of Vlčí Hora and Rybniště. The prosperous business of glass-making was first interrupted by the Hussite Wars, which were followed by the Wartemberk War with the so-called Six-Towns Alliance of Upper Lusatia in the 15th century.

Many more medieval, as well as later, glassworks are still believed to have existed. These assumptions are based for instance on local names that are still in use, and on indirect mentions found in historical sources, etc. The precise locations of these glassworks is not known, and as such presents a challenge for further research. In those places where old glassworks used to stand: i.e. in forests, near rivers, or at sites with disturbed ground surfaces, we can still find small pieces of melted glass and various fragments of ceramics used for technical and utility purposes. It is these traces that can lead to the discovery of unknown glassworks.

Renaissance

During the renaissance, the glass industry of Venice contributed to improvements in production technologies and to the development of decorated techniques, the latter referring mainly to enamel painting. Glassworks were no longer moved towards their sources of wood but had their permanent locations supported with necessary economic and human resources. Next to the glassworks in Horní Chřibská, which was managed by the Friedrichs - a traditional family of glass-masters at that time, a new glassworks was founded by Pavel Schürer in 1530 at Falknov, today known as Kytlice. Pavel Schürer came to Falknov from the Saxon side of the Ore Mountains, namely from the small town of Aschberk, today called Ansprung. Schürer was born into a family that soon became one of the most famous glass-master families in Bohemia. A few years later, Pavel's brother Jiří stood as the head of the glassworks near Krompach (before 1549). From the 1570's, these glassworks became centers of glass decoration by means of using burnt enamel paints. However, even this type of glass production was interrupted by the Thirty Years War. Soon after this war ended, the local glass industry experienced another boom period, this time during the Baroque period.

Baroque

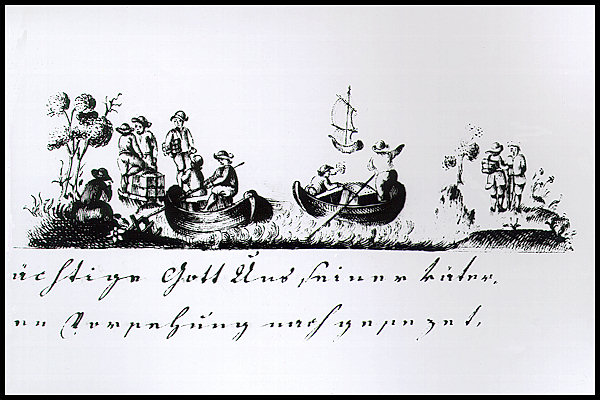

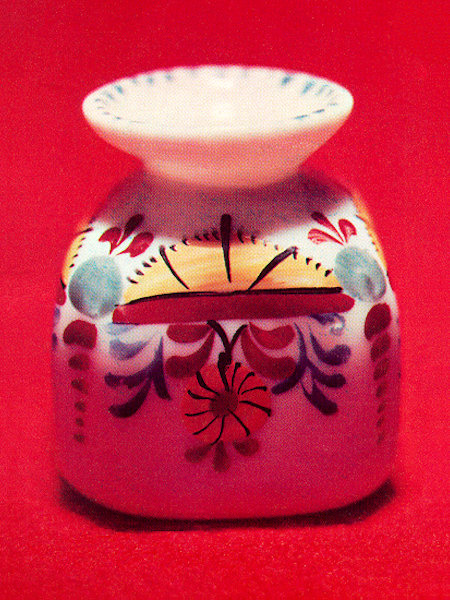

The Baroque was the period of the greatest prosperity of glass production in the Lusatian Mountains. However, compared to the previous years, the core of Baroque production was mainly glass decorate. In addition to glass painting and cutting, engraving became a widely applied method. During the Baroque period, the glass decorators from Northern Bohemia were amongst the-then glass masters who were most sought out for their exquisite abilities. However, the success of Bohemian Baroque glass-making was principally contributed to by advanced trading in glass products. The center for sales was located in this region in the areas surrounding the contemporary towns of Kamenický Šenov and Nový Bor. From this site Czech glass was exported to nearly all of Europe, and penetrated even the remote markets of America and the Orient.

In the 17th century primary glass-working was separated from glass refining. Local craftsmen obtained glass from glassworks and decorated it in their own home workshops. This type of production supported the people living in mountain villages whose modest incomes otherwise depended exclusively on agriculture. In the second half of the 17th century the first guild association of glass refiners was established, receiving the support of the local manorial nobility. At the same time, knowledge of a new type of high-quality clear glass material known as Czech crystal was spreading. Czech crystal is a perfect material for refining by means of cutting and engraving with the aid of rotating copper wheels. Around the year 1700, engraved glass from Northern Bohemia achieved a level of extraordinary quality which was retained, along with high sales, throughout the entire first half of the 18th century.

Among Baroque glassworks the most important was the Rollhütte Shop on the southern slope of Jedlová (774 m above sea level), which had been run by Jan Kašpar Kittel since about 1724. Managed by this highly-qualified owner, this profitable glass factory contributed mainly to the development of glass trading. Another glass factory located in Juliovka at Mařenice was founded in 1687 by Julius Franz, the owner of the Zákupy estate and the Duke of Saxon-Lauenburg. This was one of the first glass factories to melt Czech crystal, and perhaps also ruby glass decorated with gold. During the 18th century, glass-making activities brought about the loss of timber in local forests, which was reflected in higher prices for wood.

This was why a majority of glassworks ceased to exist during the same time period, and the production of glass was oriented on the refining of glass imported from other parts of Bohemia and Moravia, the only exceptions being the glassworks in Horní Chřibská and a newly-founded shop that was later called Nová huť (New Glassworks). The latter was established in 1750 by the glassmaker Jan Kryštof Müller in the middle of a forest north of Svor, on the site of a village that still bears the same name; i.e. Nová huť. Only these two glass factories continued to work until the second half of the 19th century when wood, whose stock in this region was exhausted, was replaced by coal.

The organisation of trade in glass was absolutely unique at that time. Traditional trading missions made by individuals were ousted by new commercial methods as richer farmers and craftsmen from foothill villages began to establish business associations called 'companies' as early as the first half of the 18th century. Being mutually bound by contract, they were able to organise and finance the purchase and transportation of raw materials more effectively. They further arranged for the refining of glass with local craftsmen who, as a rule, worked strictly according to a customer's requirements. The companies then transported finished products to foreign markets where they were sold. These business companies also established branches called 'factories' in a majority of important cities and ports in Europe and America. This type of organised business was first conducted from the villages around Polevsko, whose number was enlarged in 1757 with the village of Nový Bor, originally called Haida, and promoted in that same year to the status of a town. Most companies operated until the 19th century and made this part of the country and the Czech glass industry famous around the world.

The prosperity of Baroque glass making is further evidenced by a diverse range of production specialities. In the mid-18th century a mirror shop was opened under the orchestration of Count Josef Kinský in his Sloupy dominion. The quality of these manufactured mirrors soon matched that of the mirrors made in Paris and Venice. Another production branch developed in this region since the 18th century was the production of chandeliers, which rose to fame almost immediately. This traditional production has been maintained in the region until current times. The second half of the 18th century was marked by a crisis mainly caused by a change in customers' tastes connected with the onset of Classicism, a diminishing interest in engraved glass, the discovery of English cut lead crystal, and the failure of local businessmen to conform to new trends. This unfortunate situation was further aggravated by the blockade of overseas markets during Napoleon's wars. The best craftsmen were leaving for abroad, leaving behind others to make mostly the cheap glass affordable for ordinary - mainly village - customers. Only a small group of those who stayed behind still worked on valuable orders for gold-painted frosted glass for Oriental markets.

Glass In the 19th Century

The crisis did not abate until the 1820's when foreign markets were made accessible again and a new stage of prosperity began following the signing of the peace treaty in 1815. Coloured glass was becoming more and more popular. Glass makers in the Czech lands began to experiment with new types of coloured glass materials and refining technologies. Northern Bohemia contributed to these new developments, especially through its outstanding glass technologist, Friedrich Egermann (1777-1864). Egermann, originally trained as a glass painter, opened his own studios in Polevsko, and later in Nový Bor, where he invented and developed a number of methods which were a substantial contribution to an upsurge of local glass making tradition and to growing exports. His first inventions in the field of decorated glass were: matted, so-called agate, glass combined with fine painting; and biscuit and mother-of-pearl enamels, both developed in 1824. Egermann's studio cooperated with the best glass decorators of that time, and served as a model that stimulated the rise in the quality of glass blown in the Nový Bor region. In 1818, Egermann introduced yellow staining: i.e. colouring of the glass surface with ions of silver. In 1820, Egermann developed so-called lithyaline, which was a new type of multi-coloured glass similar to precious stones. This glass was later produced and decorated with great success throughout the entire area. However, he made his most important discovery in 1834 when he introduced red staining (colouring with ions of copper). Staining decorated mainly by engraving and cutting soon became one of the popular methods that were characteristic of Nový Bor production. This method has been used up to the present time. Egermann himself was a recognised professional. Even though his inventions spread quickly, his own studio in Nový Bor remained among the most successful glassworks in the region.

In the 19th century the popularity of engraved glass came back. The glass engravers around Nový Bor and Kamenický Šenov attained great mastery, and many of them asserted their skills abroad, for instance in France, England, and Sweden. In the second half of the 19th century, the best masters came together in a famous refinery workshop erected in Kamenický Šenov by Ludwig Lobmeyr, a Viennese businessman. Regardless of the customers' changing demands and tastes, local products continued to be made with the use of traditional methods from the first half of the century, such as refining by means of various painting techniques, staining, cutting, and engraving. Inevitably, glass from Northern Bohemia lost its prominent status, as well as influence, with the world's glass industry.

The second half of the 19th century was further marked by the establishment of the first schools of glass . The school of glass founded in 1856 in Kamenický Šenov is considered to be the oldest institution of its type in Europe. Somewhat later, namely in 1870, a similar school was opened in Nový Bor, following in the footsteps of a no-longer existing Piaristic college, the members of whose Order had aimed their pedagogical activities toward economics and the glass industry since the last third of the 18th century. Both schools were strong advocates and propagators of new artistic views on glass, thus shaping the orientation of the local industry. In these schools the education has continued until now.

The preservation of the traditional production of glass in this region is in the hands of the Museums of Glass in Nový Bor and Kamenický Šenov. The former was established in 1893, gathering the collections of local glassmakers and traders. Today, this museum - located in the town square -, offers a rich collection of glass refined through the use of local traditional methods. The Museum of Glass in Kamenický Šenov was founded between the two world wars. Its main mission is to document the development of, and to present, cut and engraved glass from this area, as well as from the production of the Viennese firm, Lobmeyr. Every three years this museum hosts a symposium on engraved glass.

Industrial Expansion in the Second Half of the 19th Century and in the First Half of the 20th Century

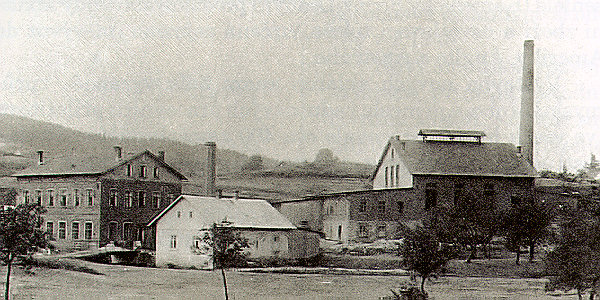

In the 1870's this region witnessed the introduction of the railroad, which made the transportation of coal - amongst other goods - so convenient. Subsequently coal began to be gasified, in which form it was used to heat glass furnaces. New technologies were soon adopted by dynamic businessmen who established a network of new glassworks to meet the needs of local glass refiners. This initiated a grand expansion of glassworks' basic industries, along with the establishment of the glassworks in the Lusatian Mountains and their foothills which did not stop until the economic crisis of the 1930's, followed by the period of the Second World War. Following the Second World War, many of these factories were not reopened.

Four new glassworks, usually named after their owners' wives, were established in Falknov-Kytlice: 'Augusta' Glassworks in 1874, 'Marie' Glassworks and 'Tereza' Glassworks in 1893, and 'Rudolf' Glassworks in 1900. None of them are in existence anymore. Other glassworks were built in Kamenický Šenov: 'Rückl' Glassworks, established in 1886 and known today as Severosklo a.s.; the contemporary glassworks run by the Jílek Brothers, which was originally put into operation in 1905; and the glassworks in Prácheň near Kamenický Šenov in 1908. The first glass factory erected in Nový Bor in 1874 was called 'Helena'; however, this factory does not exist any longer too. Another factory was known as the School Glassworks, operated by a specialised school of glass making and commissioned in 1910. Nowadays, it serves the needs of the same school again. In 1913, Flora Glassworks was built. Today it is owned by the limited liability company, Egermann. In 1893 a glass factory owned by the Rückl company was founded in Skalice, near Česká Lípa. This factory is still in operation. In Polevsko, two glassworks were erected: the first, 'Anna', in 1900 (which was later closed down); and the other, 'Klára', in 1907. In 1872, a glassworks called 'Tereza' was built in Svor (it is currently out of operation), followed by the Anna Glassworks opened in Dolní Prysk in 1907. The latter is owned by the joint-stock company, Preciosa. Of 18 glassworks established between the 1870's and 1930's, only nine have survived to see the year 2000, including the glassworks in Horní Chřibská which is still fully functional.

The Present

The local glass making industry suffered another bad blow after the Second World War due to the expulsion of the German population that included a substantial number of qualified craftsmen and skilled laborers. Mountain glassworks - traditional centers of domestic refiners - were nearly depopulated. Attempts to renew their prosperity failed, and the original glass producing villages were turned into recreational and tourist sites. After the electoral victory of the Communist Party in 1948, the process of nationalisation merged all functional glass factories into these so-called nationally-owned companies: Borské sklo in Nový Bor and Lustry in Kamnický Šenov.

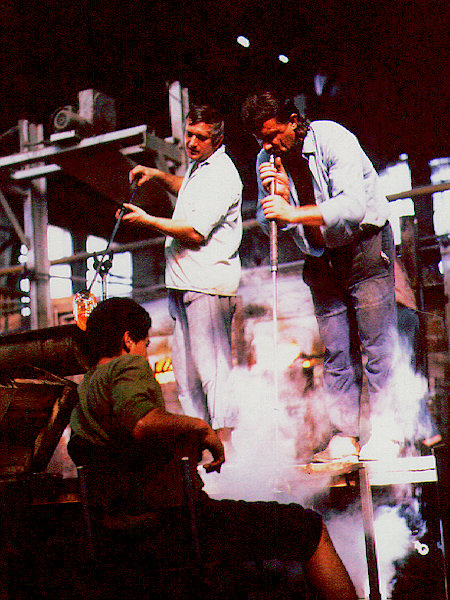

The early 1960's brought another wave of growth in the glass making industry. Indebted to the economic spirit of that time, Crystalex, a large-scale capacity workshop for glass production and refining, was built in 1967 in Nový Bor. Five years later, Kamenický Šenov became the seat of a similar factory manufacturing chandeliers. Today, this company is known as the joint-stock company, Preciosa Lustry. Mechanical production began to be widely employed. In the 1970's, Crystalex introduced the automatic production of glasses, the most successful series of which have stayed in production until now. In the 1980's, local glass making began to regain its lost prestige at the IGS international symposiums organised in a grand style by Crystalex. The results of these events are included in a permanent collection exhibited at the Lemberk Castle near Jablonné v Podještědí.

Beginning in the mid 1950's, the then-Czechoslovak glass industry began to participate in world exhibitions. Czechoslovak glass scored great successes, for instance, at these prestigious exhibitions: the Exhibition in Milano; Expo 1958 in Brussels; exhibitions in Sao Paolo, Brasil, Delhi, India, New York and Corning, America; Expo 1967 in Montreal; and Expo 1970 in Osaka. Each of these events presented, among others, glass created by leading artists from Nový Bor.

Following the fall of communism in 1989, private business activities began to flourish, and the structure of communist-type companies began to change. Like in the old days, Nový Bor and its environs witnessed the rise of home-workshops of many glass artists, engravers, and cutters. Small melting furnaces were introduced as a new means of production. Replicas and imitations of old glass patterns and styles became highly fashionable. Once again, both schools of glass apperientice, along with the glass school in Nový Bor, asserted their irreplaceable positions. A number of galleries were opened, especially in Nový Bor. The outstanding quality of craftsmanship lives through glass studios led by the famous AJETO glassworks in nearby Lindava.

The glass industry lives on in the Lusatian Mountains. It always was, and still is, in the hands of the skillful and talented people settled in this picturesque corner of Northern Bohemia. We believe this will also be true in the future.

Supplement

Those who are interested in obtaining detailed information on this subject can be recommended to the reference literature given below. Unfortunately, the majority of the books on this list are in Czech. The only work that was translated into English is: České‚ sklo, Tradice a současnost (Bohemian Glass, Tradition and The Present) by A. Langhamer and V. Vondruška, published in 1991 by Crystalex, Nový Bor. Some information in English and German can be obtained at the glass museums in Nový Bor and Kamenický Šenov. I would like to underline that the chapter on the glass-making history of this region is far from being complete, and that it is mainly a number of presupposed old glassworks from the time period between the Middle Ages and the 18th century that are yet to be found. With a little bit of luck anyone can encounter the relics of the old glass makers' activities that are hidden in the Lusatian forests and villages. Therefore we wish to ask those who would make such a finding to contact us please see our contact information). We will also be grateful for any other information, comments, inquiries, or ideas that may further improve this work.

| April 2000, Nový Bor | Jaroslav Rež in cooperation with Michal Gelnar |

Literature

1996: Turistická mapa Lužické hory 1: 75000; Geodézie ČS a.s., 1. vydání.

Bárta, J., 1931: Životopis Jiřího Františka Kreybicha, Sklářské rozhledy, roč.VIII, č.3-5.

Bárta, J., 1931: Sklářské obchodní "kompanie", Sklářské rozhledy, roč.VIII, č.7-10.

Bárta, J., 1935: Staré skelmistrovské rody, Sklářské rozhledy, roč.XII, s.71-72, 90-92.

Bárta, J., 1940: Staré skelmistrovské rody, Sklářské rozhledy, roř.XVII, č.9-10.

Braunová, H. - Rydlová, E., 1998: Sklářské muzeum v Kamenickém Šenově, Umění a řemesla, roč.39, č.3, s.14-17.

Brožová, J., 1972: Bedřich Egermann 1777-1864 a severočeské sklo jeho doby; Sklářské muzeum v Novém Boru.

Brožová, J., 1974: Lithyaliny a Friedrich Egermann, Ars vitraria,č.5.; Muzeum skla a bižuterie Jablonec n. Nisou.

Černá, E., 1987: Příspěvek k podobě zaniklých středověkých skláren v Čechách; Archeologia historica 12/87, Brno, s.405-411.

Drahotová, O., 1985: Evropské sklo; Artia, Praha.

Gelnar, M., 1996a: Staré sklárny Krásnolipska, Antique č.4, roč.III, s.47-49.

Gelnar, M., 1996b: Sklářské hutě v Lužických horách a v jejich podhůří, Bezděz, 4, s.37- 74.

Gelnar, M., 1997: Sklářské hutě středověku na Českolipsku a Děčínsku, část 1., Bezděz, 6, s.41-60.

Gelnar, M., 1999: Sklářské hutě středověku na Českolipsku a Děčínsku, část 2., Bezděz, 8, v tisku.

Jindra, V., 1991 a následující: Dějiny Nového Boru a jeho obcí. Novoborský měsíčník, příloha, Nový Bor 1991.

Jindra , V. - Ranšová, E., 1993: Sklářské muzeum v Novém Boru, katalog, Praha.

Klos, R. - Němeček, F., 1977: Skalní hrady v Českém Švýcarsku; Severočeské nakl.

Klos, R., 1997: Přehled dějin města Krásná Lípa s okolím do třicetileté války. Krásná Lípa.

Langhamer, A., 1991: Střední uměleckoprůmyslová škola sklářská v Kamenickém Šenově, katalog.

Langhamer, A. - Vondruška, V., 1990: České sklo, Tradice a současnost; Crystalex, Nový Bor.

Lukáš, V., 1974: Die nordböhmische Glashütte mit ältester Tradition I., II.; Glasrevue, č.9, 1974, s.18-21, č.11,1974, s.17-21.

NN, 1997: Lustry a lampy ze severních Čech, Antique, roč.IV, č.11, s. 26-27.

Sacher, V., 1964: 550 let sklárny ve Chřibské; Liberec, Nový Bor.

Sacher, V., 1965: Sklářské muzeum v Novém Boru; Muzeum skla a bižuterie v Jablonci n. Nisou.

Sovadina, M., 1997: Ronovci a Žitava ve 13. a v první polovině 14. století, Bezděz, 6, s.7-18.

The Museum of Glass in Nový Bor

State Regional Archives in Litoměřice, Děčín branch

State District Archives in Česká Lípa

Other graphic materials came from the private archives of M. Gelnar and J. Rež. All copyrights reserved.

On Authors

| Jaroslav Rež | Nový Bor, graduated from the High School of Glass Industry in Kamenický Šenov;

currently attends West Bohemian University in Pilsen. e-mail: j.rez@post.cz |

| Michal Gelnar | Nový Bor, part-time teacher at the High School of Glass Industry and at the

Professional School of Glass, both in Nový Bor; published several studies

on glass making, especially with regard to the Lusatian Mountains. P.O. Box 92, 473 01 Nový Bor, CZ |

Copyright (c) Jaroslav Rež, Michal Gelnar 2000

Copyrights reserved.